Protected: Place, Diversity & Interconnection: A series of three reflections (2)

Protected: Place, Diversity & Interconnection: A series of three reflections (1)

Protected: Transformative Magic: combining fire and earth to create a Living Campus

Protected: Go out and Play

TRACKS Youth Program: Amazing integrative initiatives

Since I started working for the Camp Kawartha Environment Centre, I have heard the TRACKS program mentioned almost continuously. TRACKS stands for Trent Aboriginal Culture and Knowledge and Science and is a dynamic and dedicated group of educators and activists. This summer I have been thrilled to come into greater community with them. I was extremely honoured to be part of their Tipi raising, a joint initiative with the Camp Kawartha Environment Centre. I spoke about that in my previous blog. Today, I want to speak about their outreach to kids and families through their Activity Books, Kits and Camps.

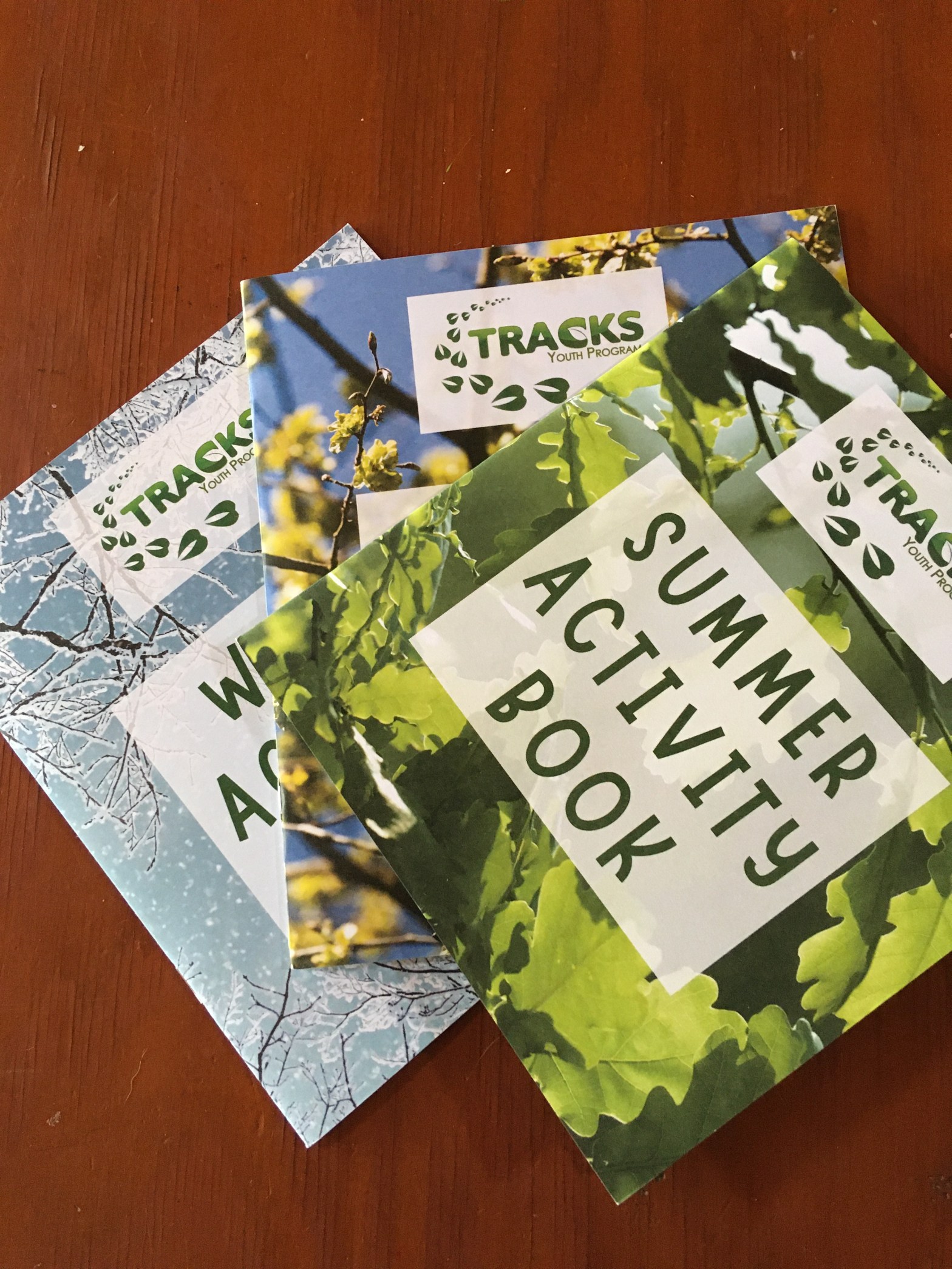

This summer, I ordered the TRACKS activity books and summer camp kits (that come with an option of joining in a virtual camp this year). I was so excited when the activity books arrived, one for Spring, Summer and Winter. For those that are interested, there a Fall activity book will be available as the seasons turn! These are beautiful books that are packed full of knowledge. What I love about them is how integrative they are: physics mixes with history, language and nature awareness in their discussion of paddles (beavertail, ottertail and square-tipped) and wiigwaasi-jiimaan (canoes) Which paddle would you choose? And would you take some aamoogaawanzh (wild bergamot) tea on your journey? There are messages for environmental stewardship (take a trip to clean up shorelines in the spring) alongside the frog cycle and tips for making a bistkitenaage (folded birch bark container) to collect sap from the ziinzibaakwawaatig (sugar maple).

Did you know that scouring rush or gziib’nashk is a nutrient rich plant that can be used to make a tea. It helps our bodies absorb Vitamin D3 and is full of calcium, magnesium, iron, potassium, copper, zinc and silicon. If you harvest some, make sure to ask the plant to share it’s medicine and offer something in return.

On a rainy day or a cold winter afternoon, pull up a chair and help Makwa (bear) find his way to his den, imagine what Tracks the chipimunk is dreaming, or search for plant words. There’s lots to do! These booklets are thoughtfully and elegantly laid out and while geared to educate kids, they are a wealth of information for adults that brings us all into greater connection with our world and the many beings that inhabit it. I am excited to try out all of these activities and to expand my own knowledge of the world right outside my door.

My son Gabriel and I did dive into the summer activity kit that arrived! There were three kits offered this year and I ordered all three: Giinzhigoong (Skyworld), Aki (Land) and Nibi (Water) kits. The Giinzhigoong kit arrived recently. WOW! What a brilliant package of goodness! This kit integrates science with traditional indigenous knowledge. The result is a fantastic kit with something for everyone. I can’t wait to see what the others contain.

In this kit, you can make a moon (Nokomis) mobile, a sun dial, make your own meteorite (using clay) and examine impact craters with marbles. There is a planetary distance activity and when you’re done that, you can choose your favourite planet (or make one up!) using a coffee filter. You can also explore the night sky using the Ojibwe Star Chart to make a constellation in a jar or make your own chart on Turtle’s back. IF you wish, you can examine the magnetic properties of the earth. Make your own compass or create your own waawaate (northern lights)! When you’re tired and want to listen to stories, use the QR code at the back to link to a Virtual Storytelling Series. All this in one box!

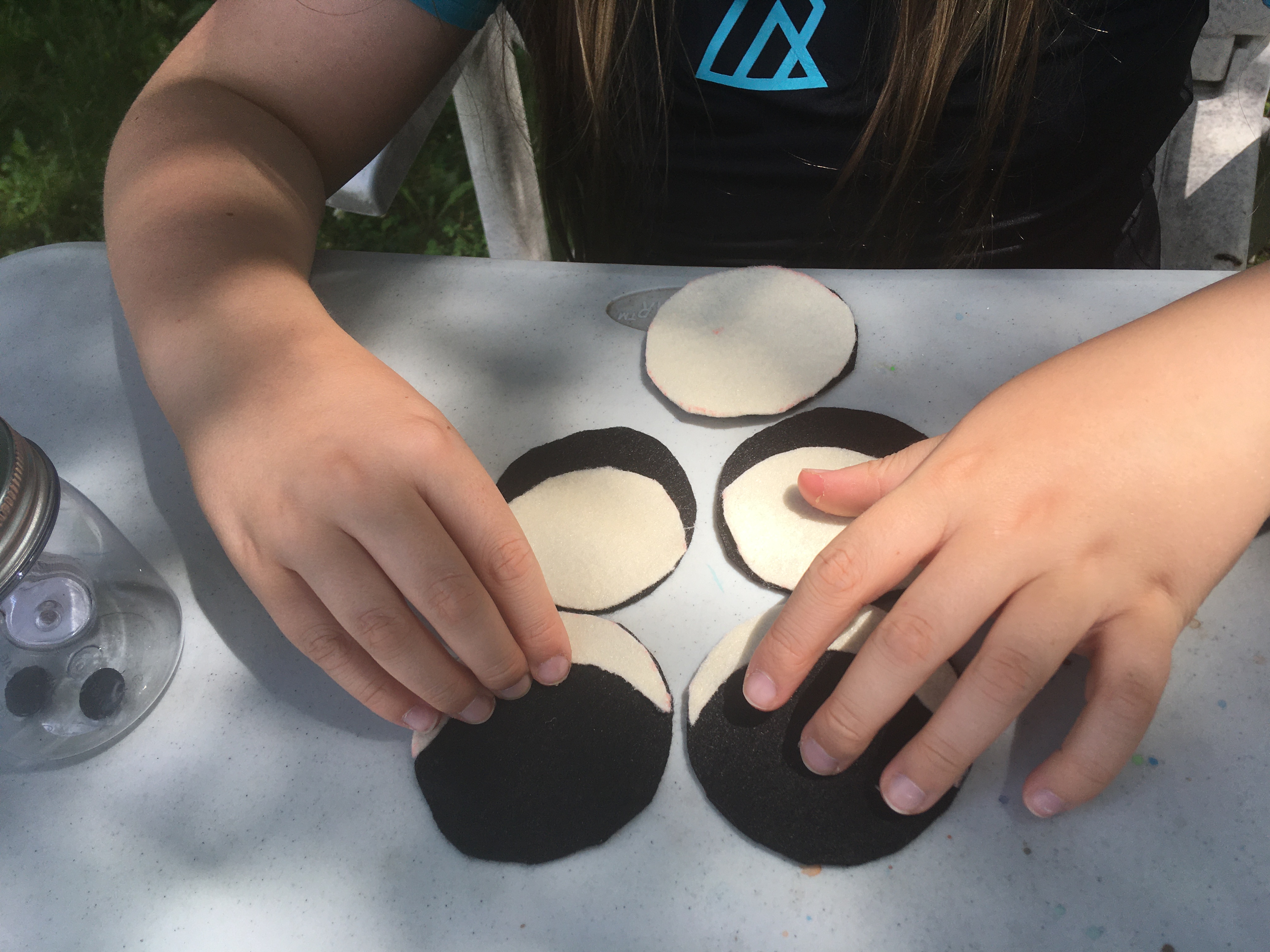

Gabriel and I worked on the Nokomis mobile. Nokomis is the Anishnaabemowin word for Grandmother and is often used to refer to the moon. The other word is dibik giizis (night sun). We took the activity outside and cut a series of circles from black and white felt. It’s always important to conserve our materials and not use more than is needed so in order to make the eight phases of the moon, you only cut out four white circles to glue on the eight black circles. There’s a trick to this that sent Gabriel thinking for awhile before the a-ha moment came!

The kit included everything but scissors and a stick! We shared the tasks and were excited by the result! We did find that the glue stick needed a little reinforcement with some liquid glue but everything else worked like a charm. I was interested to see how Gabriel took to this and expanded it! The mobile is now hung on the wall and he is tracking the phase of the moon. We added a magnetic star to the mobile to do this: sticking a plastic clear gem to some magnetic paper and using a spare small magnet to affix it through the felt. Now Gabriel can move the gem star (maybe the north star?) from moon phase to moon phase. Beautiful!

What a brilliant set of activities! These kits and books are well worth the nominal donation asked by TRACKS. If you aren’t able to make the full donation, that’s OK. There’s a pay what you can option as well. What a gift to all: ourselves and this world, to take some time to learn more about our beautiful world and to enjoy learning a little more about Anishnaabe teachings and language. Chi Miigwech to TRACKS for making these for us all to enjoy!

All information in this post is taken from the TRACKS Youth Program Activity Books (Winter 2020, Spring 2021 and Summer 2021) and the Giizhigoong kit (2021). For more information on these books and kits, please visit the TRACKS website

Reference List.

TRACKS (2020). Winter Activity Book. TRACKS Youth Program.

TRACKS (2021). Spring Activity Book. TRACKS Youth Program.

TRACKS (2021). Summer Activity Book. TRACKS Youth Program.

TRACKS (2021). Giizhigoong Kit Booklet. TRACKS Youth Program.

Raising a Tipi: An invitation to community

I got up early on Friday, June 11th, to bike up to the Environment Centre. It was a very special day for me. I had been invited to participate in raising a Tipi at the Camp Kawartha Environment Centre with TRACKS (TRent Aboriginal Cultural Knowledge and Science). This was a joint venture with Camp Kawartha to strengthen community ties, share knowledge and support Indigenous knowledge keeping.

When I rolled into the Environment Centre, it was already a hub of activity. David Lundberg had driven down from his home and workshop in Timmins (Sewn Home) with everything we needed to raise the tipi. People had begun to move the long spruce poles from the circular drive of the Environment Centre to the place where the tipi would be raised. I parked my bike and joined in. The poles were not heavy but at about 30 feet long, you needed to be watchful and plan your route. I bumped into a few bushes going ‘round the birdfeeders the first time! What a wonderful feeling, though, to be out in the world, building a community space. I loved the weight of the spruce beam on my shoulder and, when it bounced, I could feel the strength and flexibility of this tree that would lend these important qualities to the tipi.

David told us about how the spruce were harvested. He spoke about creating relationships with the loggers in the Timmins region and how he was able to go into the long corridors and clear cuts to harvest this spruce. He spoke about how spruce likes to grow together, in communal groves, so that the tall slender trees can support one another against the wind. He told us that he was able to go in and sustainably harvest those trees damaged by the logging process. I think about the seedlings my WILD group planted out front and wonder about how best to care for them. Should we plant more? How should we best support our tree friends? This is a question I have been asking increasingly as I become more aware of how integrated our planet is.

Community is everything and I look around at the people gathered to learn from David and Billy, an elder who will lead a fire ceremony in the tipi later this day. There are our Environment Centre people, the TRACKS folks in their fabulous T-shirts, and Rodney, a local film-maker who will document this day. It is good to be here, with old friends and new, learning and creating this place together. I hope that we will all be like the spruce trees that will make this tipi, finding strength through standing next to one another, so that when the winds blow, our inter-connectedness will strengthen us and let us reach toward the sun. This is especially important right now, with light being shed on the horrors of residential schools, something very much in my heart throughout this day.

David directs us to find the four strongest poles, three of which will become the main supports for the tipi and the fourth which will raise the canvas. It is like an elegant dance: the three poles are laid out, two together and one angled off to the side. They are measured and cut. Precision matters here and David emphasizes the importance of this to the strength of the tipi. The angled pole is cut slightly shorter than the other two to ensure that everything lines up when the other poles are added.

The poles are tied together with a series of clove hitches. Clove hitches are one of my favourite pieces of knotwork. I was taught them by my Dad who used to work on the docks at Goderich when he was boy. Here, they are used to both secure the rope initially and at the close, but also to tighten the ropes to hold the three poles together. Modern technology makes an appearance as David secures the ropes with some screws, additional security at a key structural point.

Then the magic happens. The rope is pulled, and the tallest members of our crew begin to walk the poles upright. Feet are used to brace the spruce poles and soon there is a triangle towering overhead: still two poles on one side and the rope pole on the other. Careful now and steady. David takes one of the two poles and walks it calmly out to where it can form a tripod. The crew can let go. With its three legs securely on the ground, the tipi will not tip over.

David makes more measurements to ensure that the triangle base between the poles forms an equilateral triangle. Precision now will ensure safety and the longevity of the tipi. These poles will support the entire structure, grounded in their support of each other.

Then the additional poles are added, one by one, feet bracing them until they are in position. Then they are roped together, using the original rope. David walks around the tipi, snapping the rope into place and tightening it to hold the poles together. He then winds it down its original pole (used to raise the tipi) and secures it in place with another clove hitch.

Break time and crew shift time. These are Covid times and we’re careful of distance and the numbers of people able to be together today. I munch on some food graciously provided by TRACKS and the Environment Centre. I get to chat with a few people I don’t often see in these times. What a wonderful treat! Then I help do a bit of cleaning and water our trees out front while the canvas is raised and secured around the tipi. I missed this part but I did get to see it going up through the Environment Centre window!

I was again able to join in to help secure the canvas, again with ropes as well as pegs to hold it to the ground. I am always in awe of the strength of knots. We don’t teach much knotwork and, yet, for me, it’s been an essential part of my life, holding canoes on cars and even a muffler (tied with ethernet cable of all things). It doesn’t take much technology to make things secure. Ropes can often be a better choice than screws or nails.

The tipi is up, beautiful and white against the green of the trees and the changing blues and greys of the sky. Rodney gets his drone going and takes some shots of us waving. We wave and wave and wave. Then he says: “OK. I’m ready! Wave!” We laugh a wave some more.

It is time now for the fire ceremony, for this tipi to begin it’s journey in connecting and centering communities. This will be a day I will remember always, for it’s beauty and synergy and connection with the land and people that live in Nogojiwanong. Chi miigwech to all those at TRACKS for the invitation, to Craig for holding this space, to David and Billy for sharing their knowledge and all those who shared their time and energies to build this beautiful place.

Three Sisters: Moundbuilding and Storytelling

“It should be them that tell this story …” (Kimmerer, 2015, p. 128).

Robin Wall Kimmerer is an inspiring storyteller, scientist, mother and Indigenous activist. It is no wonder that that our EDUC6106 (Indigenous and Global Perspectives) has gravitated towards her book, Braiding Sweetgrass (2013a) to explore our own journey in understanding and reconciliation.

One of the ideas I wanted to explore was the three sisters garden. I’ve long been a fan of companion planting and the science behind plant intelligence and communication is awe-inspiring (Kimmerer, 2013a; Simmard, 2021; Simard, 2016). I thought this would be an ideal time to explore this with my son. Not only will we try for three gardens (at home, at our community garden and at the Camp Kawartha Environment Centre), we will also be participating in a community of gardeners whose experiences in this venture will be celebrated and shared. Community and reciprocity, giving and receiving, sharing and learning, these are some of the main ideas that both Kimmerer (2013a) and Simard (2021) observe in plants. These are gifts they can give us, if we’re patient and quiet enough to listen.

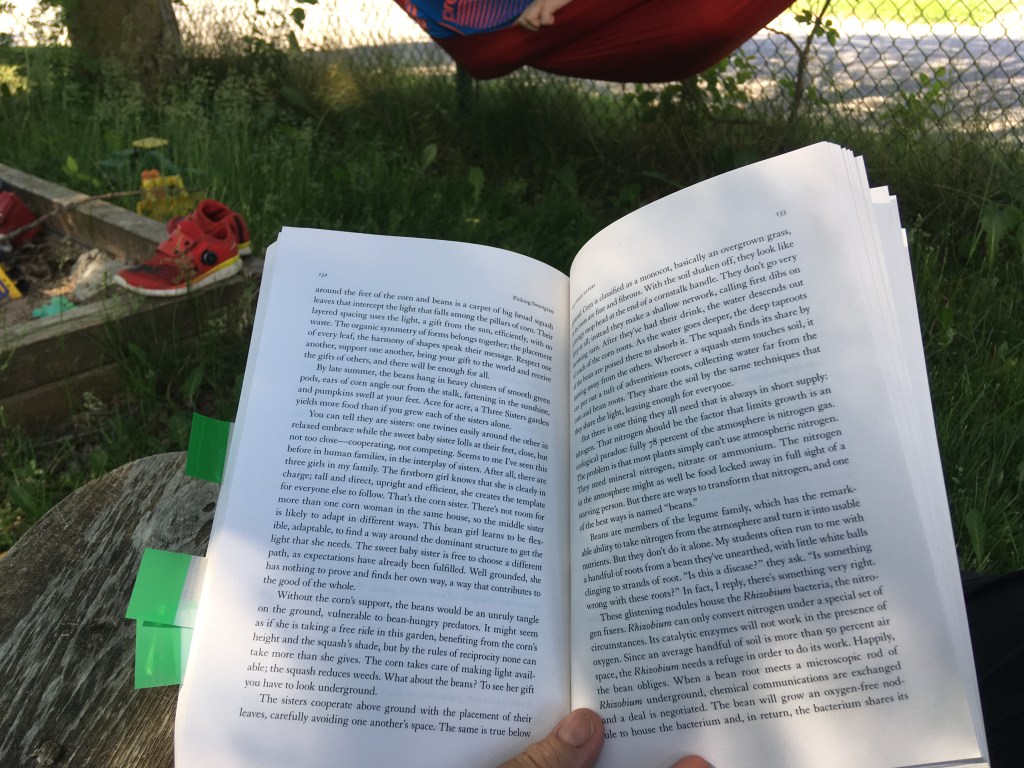

It all began on a warm day in early June. Well, it began long before that, but we’ll start this story here, with Gabriel swinging in the red hammock with the ash trees whispering overhead. The robins are singing and there is the long coo-hoo-coo-coo-coo-coo of the doves. The sun is warm where it flits between the leaves of the ash and rowan in our backyard. It hasn’t rained in awhile.

I settle into the white cedar chair I made for my Dad long ago and open Braiding Sweetgrass (Kimmerer, 2013a) to page 133 and begin reading: “It should be them that tell this story …”. Gabriel listens to the story of corn, the first sister, emerging from the ground, shooting up quickly like the grass it is. He hears about beans, the middle sister, and how they dig their roots deep, grow leaves and then tendrils to grasp onto corn. And the third sister squash, a little slower than the others and determined to go its own way in the world. He learns that corn grows tall but has shallow roots that love water, that beans contribute nitrogen to the three sisters through cooperation with the Rhizobium bacteria, and that squash shades the soil from the sun and reduces weeds. All contribute their own special gifts and enrich the lives of the others that grown near them (Kimmerer, 2013a, pp. 128-134).

Which is where the story of the three sisters comes in: they who arrived on a winters night when the people were dying of hunger, one robed in yellow, another in green and the youngest in orange. Even though there was little food, the people shared what they had. In gratitude and reciprocity, the sisters revealed that they were corn, beans and squash and gave seeds to the people so that they would never grow hungry (Kimmerer, 2013a, p. 131). A story of biological and social reciprocity.

As I write this, I wonder about the origins of this very important story. Does it tell of the beginnings of agriculture? Of communication between different groups of people? What other stories are there to be told about the arrival of the three sisters? Archaeologically, squash and beans were the first sisters, with evidence of domestication in Mesoamerica and South America respectively between 7000-8000 BC with corn (evolved from teosinte) joining them between 2000-3000 BC (Price & Feinman, 2003, p. 197). Peoples in Eastern North America appear to have another three sisters: squash, marsh elder and goosefoot (chia) around 2500 BC (Price & Feinman, 2003, p.254-55). Corn made her way north from 1200 BC in the southwest to AD 1-200 in the Eastern Woodlands (Price & Feinman). These are stories of human reciprocity with plants, choosing and selecting and observing how plants grow and slowing linking our own evolution and social interaction with theirs in a dance that has changed both communities. In the Western capitalist practice of monoculture, this dance has become less about cooperation and more about coercion. The story of the three sisters, aiding humans in times of starvation, is one we should all listen closely to.

Seeking to understand this story of cooperation, my son and I head off to our community garden where I mound the soil and rake it and make gentle craters in the tops as the webpages I researched suggested (list webpages). I ask my son if we should follow the webpages advice and plant corn first. He shakes his head. “No! That’s not what the book said. Beans take time to grown their tendrils. Let’s plant them all now”. There is, of course, some 9 year old impatience in this statement but Kimmerer doesn’t tell of planting separately and it is her story we’re following (though later I read another article by her which says to plant corn first! (Kimmerer, 2013b). And we learn as we go. And modify for next year. If this works and my son gets fresh corn to slather with butter and salt, we’re going to be growing this sister for a long time to come!

My son helps me plant. Together, we put the corn in the top, marking the four directions. The beans are planted in the mound and the squash at the bottom. My son insists on planting a squash (we chose pumpkin and butternut) along the edge of the garden. I shrug and don’t comment. We will both learn if this is a good idea and whether this third sister can be convinced to grown around the mound rather than across the path and out of the garden! The sun is hot and my son is beginning to wonder when we will be be done. I think about the women long ago planting the corn, beans and squash. Were their children equally impatient? Or were they dedicated participants, understanding that this was important to how loudly their bellies would complain come winter? Would my son even have been part of the growing, or would he have been learning about hunting and tracking, the latter which I find fascinating but my son has little time for! Gardening has an eventual treat. But we are not hunters and deer tracks don’t mean food but a boring trek through the woods where you must remain quiet and not talk. Deer are also large and fast for all their silent, shy natures.

But here, in this garden, there are no deer, but a community of curious and dedicated gardeners. Our mounds look like something old and ancient next to the neat rows of lettuce and carrots. As we water our mounds, the water pours off the dry dirt, bonding with it and taking it with it, leaving dry slopes. I wonder if I have made the mounds too steep or if we are seeing the dusty dry nature of June this year. Time will tell. And the experiences of my other colleagues making gardens of their own.

Reference List

Kimmerer, Robin Wall. (2013a). Braiding Sweetgrass. Milkweed Editions.

Kimmerer, Robin Wall. (2013b). The fortress, the river and the garden: a new metaphor for cultivating mutualistic between scientific and traditional ecological knowledge. In Andrejs Kulnicks, Dan Roronhiakewen Longboat & Kelly Young (Eds.), Contemporary studies in environmental and Indigenous pedagogies. A curricula of stories and place (pp. 49-76). Sense Publishers.

Price, T. Douglas & Feinman, G. (2003). Images of the Past. McGraw-Hill Education.

Simard, Suzanne. (2021). Finding the mother tree: Discovering the wisdom of the forest. Allen Lane.

Simmard, Suzanne. (2016, August 30). How trees talk to each another. TED. https://www.ted.com/talks/suzanne_simard_how_trees_talk_to_each_other?language=en .

Protected: Creating Chocolate Cells

Food for Thought: Reflections on the Food Challenge

When I first read about the Food Challenge for my new course Education for Sustainability and Entrepreneurshipover the Christmas break, I got very excited. There were little firecrackers going off in my brain. There was so much scope here, and so much I wanted to do. I deeply believe that our relationship with food needs to be changed in order to make our relationship with our planet a healthier one (Robinson, 2020, Shiva, 2012; Warhurst, 2012).

I thought about making a meal from foraging and even went on a lovely walk with friend to start that process. I thought about growing greens. About doing a cool integrative learning project with my son, Gabriel. All those ambitions are still in the works, but what I actually accomplished was soup… with a side-dish of creative chocolate cells as a Genius Hour desert! The starter and the finish of a marvellous meal and a continuation of our household’s shift towards a more sustainable lifestyle.

The underlying motivations for this soup challenge were many. A large part of the inspiration to take this MEd stemmed from a real desire to practice sustainability and to change my relationship to the planet. I was truly inspired by the consumption journal we did for the course Foundations of Sustainability (EDUC6101) where I highlighted the fact that we buy a lot of good quality soups for my Dad (who has swallowing difficulties). This results in additional money being spent from our household budget, increased recycling and food waste, less nutrition and increased separation from our food sources. This was something we could easily do something about by making our own soups. I wanted to tie the courses and knowledge together to move reflection into action. It worked!

The other theme running through this is expression of knowledge and experience through social media. Again, the stimulus (though not the desire) has come from the two MEd courses, where blogging and videos play a large part in course activities and research. The pandemic has increased this emphasis on the spoken word and on visual media as important and easily accessible ways of interacting with the world that are now on, if not equal footing, certainly in a more balanced relationship with the written (and often peer-assessed) word. As the Department of Education’s (CBU) mission statement notes (Campbell unpub), education has an important global context in today’s world. Social media plays an essential role in communicating sustainable practices and advocating for change. The use of this blog to record a series of posts on Soup for the Soul reflects my commitment to bringing my ideas, experiences and knowledge into a wider social context (Juliani 2015, p. 19; Wettrick 2014).

It has certainly started a conversation in my own mind. And I see this project as one step on a longer a journey. The dish I wasn’t able to make in this time frame was the middle one of the main meal. This is the dish that I envisage would have come from our garden, the forest and local growers. It is perhaps a better one begun with spring and summer approaching. And it is, in the end, a deepening of a commitment our family has already made. I want to stretch this, in small ways, to increase our connection to our world and the communities that inhabit it. I am looking to be inspired by my colleagues in this course as to ways in which to do so.

The Value of Reflection: What have I learned from this project, how would I have done things differently, and what am I bringing to future projects

This course is asynchronous, meaning that deadlines are soft and encouraged to be met. This aligns both with the practical considerations of many of the students with regards to full-time jobs and families and with a different model of education where investment in creativity and belief in student accomplishment produce exceptional results. This assignment has gone far past its suggested deadline. There are reasons for this. During the time I was doing this food challenge, a number of unexpected happenstances occurred, the primary of which was that my Dad had a nasty fall and ended up in the hospital. There was a considerable shift of energies during this time towards managing (often remotely) his hospital stay.

This project has been about slowing down, reprioritizing and taking the time to connect with food. However, in these last couple months, it is as though the world has sprouted with opportunity for connection, like the flower buds on the maple outside my window. Participation in the MEd has also resulted in being introduced to a wide variety of educational endeavours in the form of conferences and working groups engaged in creating more integrated education environments for students. These are not to missed! But, equally, they demand time. This has become heightened during the pandemic where our social existence has shifted online and where it is now possible to attend virtual conferences globally and throughout the day and night. This is an incredibly important and exciting time for education, underlying the importance of expression through social media platforms (including Zoom). Balance between course expectations and educational opportunity was difficult through this time and only made possible through the asynchronous aspect of this course. I have a great gratitude to Liz and my colleagues in this course for holding this space to allow for participation in all of the other exciting discussions happening on a global scale.

These global discussions and vigour have also been reflected locally. Opportunities for the course I teach at the Camp Kawartha Environment Centre flourished (in part through integrating the knowledge gained in this course about student agency and virtual communication). WILD: Wildlife, Wild Places and Wild Issues is a course created pre-pandemic with a mandate towards community involvement and action. We haven’t been able to access many of the like-minded community groups that we did last year and the course has somewhat floundered. However, a recent exploration into liaising between the two Camp Kawartha sites, discussion with a local film-maker (and parent), and discussions with my mentor, friend and boss, Craig Brant, a whole range of activities and opportunities have opened up. This has also demanded a fair amount of time spent in highly invigorating meetings. Equally, because of it’s success (I am pioneering a number of new options for students, especially older students in outdoor education at the Environment Centre), there have been additional difficulties that have arisen that had to be addressed with care and patience.

What I have learned from this, is an awareness of the need to shift the focus of my MEd projects to a smaller scale, if not greater scope. This is difficult for me. I am a big ideas person! Thankfully, I am in the right place for big ideas, and am supported both by the ethos and members of the Education Department at Cape Breton University (see O’Brien, 2016, p. 209) as well as my amazing work environment at Camp Kawartha where the value of dreams is seen and encouraged every day. However, ‘aiming ridiculously high and playing with Big Ideas’ (O’Brien, 2016, p. 209) needs to be tempered with an acknowledgment of time, both in terms of saying ‘Yes’ to impossible schedules (as I did here) and acknowledging limits (as perhaps I should have done more of). For me, picking one thing rather than a series of things (such as these soups), needs to be considered in the future. Or perhaps, simply a different way of framing the expectations and end result.

This said, would I have done anything differently for this project in terms of its scope? I think not. The whole aim of this was to shift a practice from buying soups to making soups. While I could have done a one-off recipe, that doesn’t make a habit. It was essential to enact a practice of shifting behaviour towards more a more sustainable relationship with the planet.

What I could have done differently was recognize that the time scale was going to be longer and to openly submit a ‘progress-so-far’ report on time so that my class colleagues could engage with it and comment in a timely fashion for them with the end result being submitted later. Dr. Liz Campbell has been incredibly supportive of individual learning trajectories and this would have been a viable and encouraged option. Furthermore, having my colleagues comment half-way would have immeasurable benefit. Finally, this route would have further challenged the status quo of projects being assessed primarily on their end result rather than the journey of creating them. This works with the understanding is that it is experience that is our best teacher and that learning occurs best when mistakes and reflection are allowed and encouraged (Boaler, 2019, pp.26-78).

Going forward into the MEd, I will bear three aspects in mind: reducing the scope (if not the Big Idea), putting more emphasis on process, and looking for ways to increase communication with my colleagues. I missed out greatly with this because I have been stubbornly trying to finish rather than posting a progress report. In future, too, I will try to bring these projects into closer relationship with both the teaching of my WILD course and the homeschooling of my son (see the blogs on the Genius Hour project). This will enrich all our lives immeasurably!

Food for Thought: Thinking deeply about the role of gratitude in sustainability

Gratitude, in the end, has played an integral part of this project. Gratitude for the food that I eat, for the time I have taken to make these soups, from the gifts of kitchen items and of the food itself, and gratitude for the time taken and given for this project. It has been a project of community as well as individual endeavour. And it has taken an idea articulated in the fall and carried it through into a reality. I couldn’t be happier.

This journey of Soup for the Soup was in spirit of taking small steps, on focusing on the local and the everyday. I am inspired by the example of tiny houses (of which I recently had a virtual tour!) where life is pared down to essentials and where creativity and beauty abound in the challenge of how to make modern life flourish in small spaces. I think this also applies to projects and I am looking forward to encouraging my thinking towards this ideal. Sustainability is not just about buildings and food, it is also about time and lifestyle.

These soups have certainly brought our family into a better balance, with less money spent on food, less waste produced and more compost created! They are more highly nutritious! There is a gratitude to be given here as well, to Liz for her inclusion of the food challenge and unwavering support, to my MEd colleagues for their inspiration and conversation, for the gifts my friends have given, and to myself for carrying on and completely this vision. The challenge will be to continue the practice of making soup. Community will be important in that and taking the time to invest in our family and our planet.

Food is about community and gratitude. We come together to gather, to grow and to eat. I think it is in connections between people that we see the most scope for change and for enriching our own lives. Every small step makes a difference and many small steps make a journey. Thanks all for being on this journey of small steps, of leaps and bounds and sideways dances. Be well!

Reference List

Boaler, Jo. 2019. Limitless mind. Learn, lead and live without barriers. Harper One.

Camp Kawartha. (n.d.) Environment centre. Camp Kawartha. https://campkawartha.ca/environmental-education-centre/.

Campbell, Elizabeth. (2021) EDUC 6103: Education for sustainability and entrepreneursip. Unpublished Course Syllabus.

Juliani, A. (2015). Inquiry and innovation in the classroom: Using 20% time, genius hour, and PBL to drive student success. Routledge.

O’Brien, C. (2016). Education for sustainable happiness and well-being . Routledge.

Robinson, Ken. (2020, August 23). Creating a new normal. . The Call to Unite. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lUvNTt6crFM

Shiva, Vandana. (2012, September 25). Solutions to the food and ecological crisis facing us today. TEDxTalks. https://youtu.be/ER5ZZk5atlE

Wettrick, D. (2014). Pure genius: Building a culture of innovation and taking 20% time to the next level. Dave Burgess Consulting.

Warhurst, Pam (2012, May). How we can eat our landscapes. TEDSalon London Spring 2012. https://www.ted.com/talks/pam_warhurst_how_we_can_eat_our_landscapes?utm_campaign=tedspread&utm_medium=referral&utm_source=tedcomshare.